Stories

— In depth, intimate photo essays and explorations

Christy Shake guides her son Calvin Kolster from the school bus to their home in Brunswick, Maine on September 29. 2017. Calvin is thirteen, in the seventh grade, and has severe epilepsy and autism. He is also legally blind. “I have to be forever watchful," she says. "I feel like it’s probably like having a baby that’s learning how to walk but can’t quite walk yet and you can’t leave….It’s sort of that type of vigilance, but it’s thirteen and a half years of that vigilance.”

Christy Shake feeds her son Calvin his afternoon dose of cannabis oil mixed with yogurt on October 8, 2017. Christy purchases the cannabis and then takes the plant matter through a lengthy process to create a resin which she then suspends in oil. She feels the cannabis does have some effect on the seizures, but its real benefit is curbing the severe side-effects of the benzodiazepine withdrawal.

Christy Shake sits at her desk and reaches out to her community through social media to find help walking her dog Nelly as her son Calvin hangs out in his jumper a few hours after having a grand mal seizure on September 30, 2017 in Brunswick, Maine.

"He has his favorite spots." Christy Shake blocks her son from biting at the siding on a neighbor's house while their dog, Nelly, looks for squirrels in the yard on October 8, 2017 in Brunswick, Maine. Calvin is very tactile and likes the feeling of his teeth against hard surfaces, and, because of his very poor vision, he is drawn to clear patterns of contrasting light and dark.

Christy Shake walks behind her son Calvin up the stairs in their home in Brunswick, Maine on September 30, 2017. Though Calvin can walk on his own now, his balance and vision are not good, and he can easily fall without Christy nearby to catch him. Much of their routine when he is home consists of her following him from room to room.

Christy Shake cuddles her son Calvin in his bed a few hours after he has had a grand mal seizure on September 30, 2017 in Brunswick, Maine. Though his number of daytime seizures has decreased dramatically since she began treating him with cannabis, he still has grand mal seizures in the early morning hours almost weekly.

A jar of cannabis tincture sits on the counter after Christy Shake has strained the plant matter from it. The tincture will be suspended in oil and used the alleviate some of her son Calvin's symptoms.

Christy Shake braces her son Calvin as he looks out the window of their home in Brunswick, Maine on September 30, 2017. Though Calvin can walk on his own now, his balance and vision are not good, and he can easily fall without Christy nearby to catch him. Much of their routine when he is home consists of her following him from room to room.

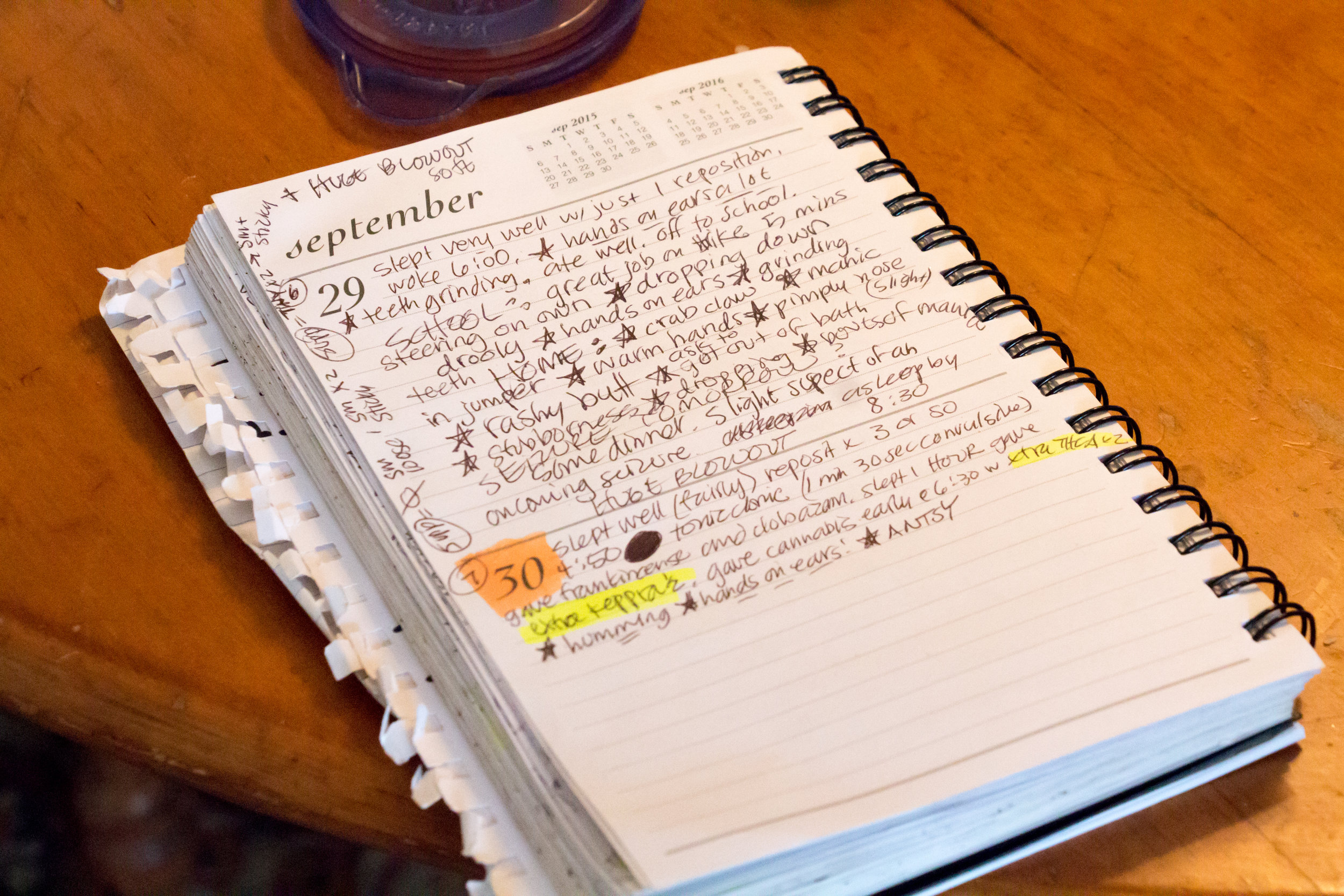

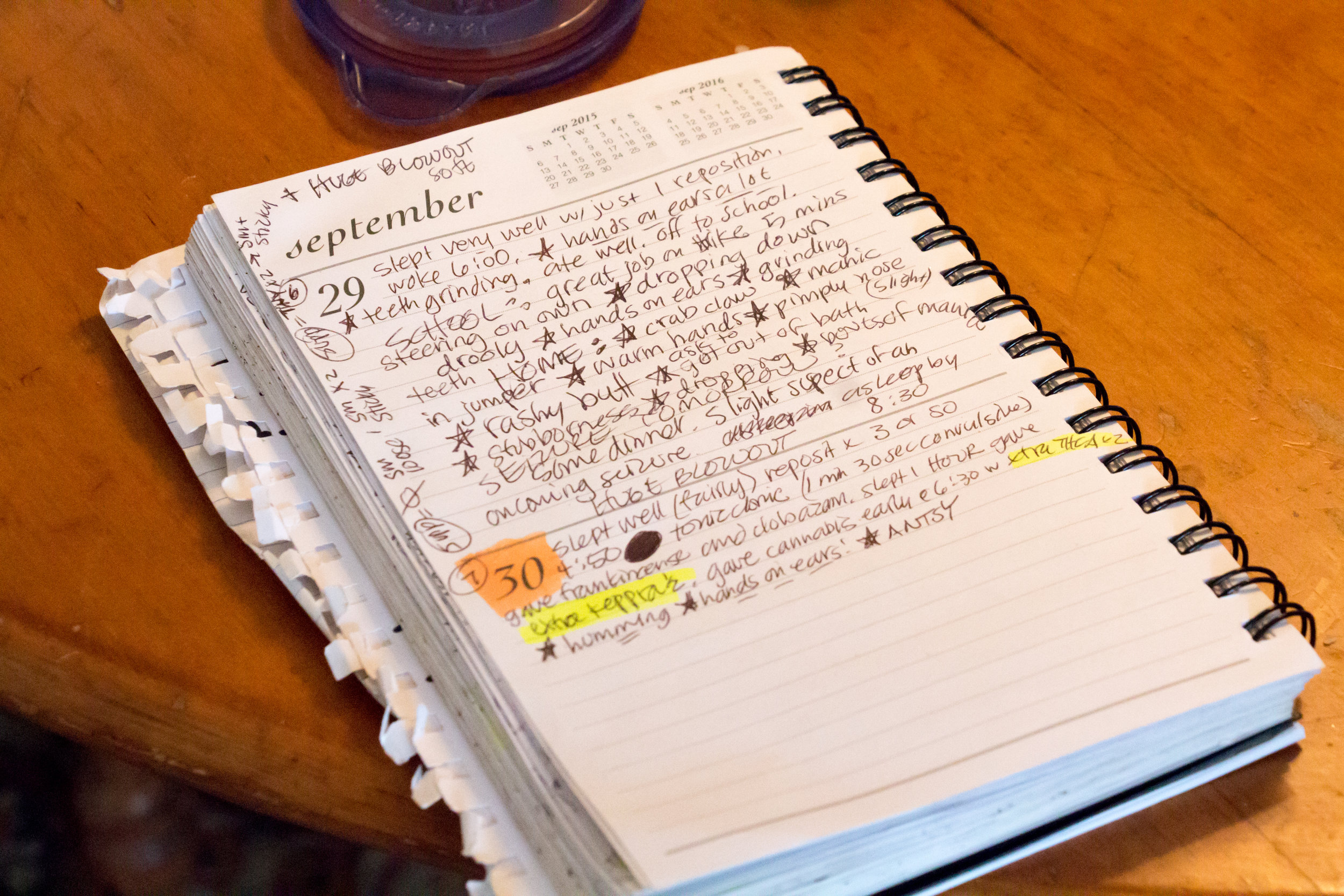

For most of her son's life Christy Shake has kept a detailed daily log of her son’s behaviors, his medicines, his symptoms, his bowel movements. The notes have helped her learn to predict when a grand mal seizure is imminent. Several stars are a warning and orange highlighter indicates a grand mal seizure.

Calvin Kolster of Brunswick, Maine enjoys spinning himself in circles in his jumper that hangs from the dining room doorway of his house on September 29, 2017. When Calvin was a baby, the doctors said he likely wouldn’t walk, talk, or crawl. At eighteen months he said “momma” for the first time. Not long after, he had his first seizure and never said another word. At two years old, he was diagnosed with severe epilepsy. At three years old he was prescribed his first valium. Now, at thirteen, he is in an active benzodiazepine withdrawal, the symptoms of which are treated with cannabis.

A portrait of Calvin hangs above a dresser covered with medications and medical supplies in his bedroom on September 30, 2017 in Brunswick, Maine. Calvin doesn't sleep very well and wakes up several times a night. Christy gets up to soothe him, cover him with his blanket, or give him a dose of medication.

Calvin Kolster plays in his bed on a rainy Sunday morning in Brunswick, Maine on October 8, 2017

Christy Shake works in her yard with a baby monitor close to her ear so that she can hear if her son Calvin wakes from his nap in Brunswick, Maine on Sunday morning, October 8, 2017.

Christy Shake writes at her desk in her home in Brunswick, Maine on October 8, 2017. For seven years she has been prolific in her blogging about her son and his story. She looks forward to writing and answering questions from other parents of chronically ill children.

Calvin sits in a rocking chair eating a piece of chocolate at a neighbor's house on October 8, 2017 in Brunswick, Maine. Since reducing his benzo dose and adding cannabis to his treatment routine, Christy says Calvin has become calmer, more mobile, and easier to take places. Often they walk down the block to check on their elderly widowed neighbor Woody.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, a system of two-foot gauge railroads connected rural areas of Maine to the bigger cities in the state. Since 1992, the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad Museum has been educating tourists and locals about these rails from their location on Portland’s waterfront.

In addition to the artifacts in the museum, at the top of each hour, patrons can board one of several restored train cars and experience a little of what a ride on the narrow gauge was like in the past. A coal powered steam engine chugs along the base of the Eastern Promenade park giving visitors a panoramic view of the Casco Bay.

In 2009, the property that holds the museum’s lease was listed for sale, and the future of the museum in its current location at the historic Portland Company complex came under question. The Board of Trustees reached out to other communities across the state, and in 2011 selected the town of Gray as the new home of the Maine Narrow Gauge Museum. Delays in the development of the current site and on-going fundraising for the building of the new site have postponed the move for some years. But as the official 2017 season came to a close, it was still uncertain if the museum trains of 2018 will be offering views of the Casco Bay or the rural marshlands of Gray.

Passengers and Volunteers take the last ride of the 2017 season on the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad’s train in Portland, Maine on October 29, 2017.

Passengers and Volunteers take the last ride of the 2017 season on the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad’s train in Portland, Maine on October 29, 2017.

Passengers and Volunteers take the last ride of the 2017 season on the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad’s train in Portland, Maine on October 29, 2017.

Passengers and Volunteers take the last ride of the 2017 season on the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad’s train in Portland, Maine on October 29, 2017.

Passengers and Volunteers take the last ride of the 2017 season on the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad’s train in Portland, Maine on October 29, 2017.

Passengers and Volunteers take the last ride of the 2017 season on the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad’s train in Portland, Maine on October 29, 2017.

Passengers and Volunteers take the last ride of the 2017 season on the Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad’s train in Portland, Maine on October 29, 2017.

Live action role-playing, or LARP, combines community, creativity, improvisational acting, and physical play to create fictional worlds full of characters who interact face to face under an agreed upon set of rules. Larping encompasses various genres with groups reaching across the globe from a large scale organizations to smaller local units.

“There’s a certain kinship to it,” says a member of a local Portland, Maine unit whose character’s name is Thanadar. “If you ever were to come out to one of our practices….we have transgender members, we have a lot of alternate lifestyles…. It’s a very accepting community where people can come and feel safe.”

Kevin Dillard, aka Caseus the Iron Turtle, aka Burlap the Beggar grabs breakfast at Burgundar, a LARP specific recreational site on September 17, 2017.

Adikan Rafenson, left, uses a foam weapon while sparring with unit-mate Adomos (right) at Burgundar on the morning of Septermber 17, 2017.

Rules for garb vary among units, but most members make their own costumes. Research and historical accuracy are highly regarded when it comes to dress.

“We call it Arts and Sciences. What we make our garb out of isn’t just because they used linen back in the day. I use this linen specifically because it breathes really well because of it’s loose weave,” says Thanadar.

Shoes belonging to Adikan Rafenson.

"Casin over there, I’ve known him off and on for a while. He and I get along on a lot of different levels, and so I’ve taken to calling him brother recently….We understand each other." Kevin Dillard on the strong bond he has developed with members of his unit.

For 8 days every summer, Dagorhir chapters come together in Pennsylvania at an event called Ragnorok. Participants fight in battles, sell and trade crafts, and socialize with other larpers. "My life is Ragnorok, my birthday, Ragnorok, " says Kevin Dillard.

Kevin Dillard shows off his persona Caseus the Iron Turtle and all of the items he has made and collected for his kit. The shaman shack, Burgundar, September 18, 2017.

Garlands of bones dangle from the roof of the Shaman Shack at Burgundar, September 17, 2017. The site, located near Harrison, Maine, is dedicated for use by different larping groups in the state.

Trinkets and tokens memorializing six years of larping with Dagorhir hang from the staff of Caseus the Iron Turtle.

Rowena (Courtney), Adomos (Bradley), and their one year old son Begivenhad (Jensen) . "I don’t do any fighting. But every now and then I’ll go out, and I’ll spar with someone," Rowena says. "We do have families starting in our unit. We have a child, and we have another unit mate who’s expecting a child with their girlfriend."

"These are the people I connect with on a different level. This is why I do this." says Thanadar at Burgundar, September 16, 2017.